91st Infantry Division - Powder River

Activated 15 Aug 1942 • Entered Combat 9 Jun 1944 Rome • Days of Combat 271 • Casualties 8,744

Commanding Generals

Maj. Gen. Charles H. Gerhardt Aug 42

Maj. Gen. William G. Livesay Jul 43

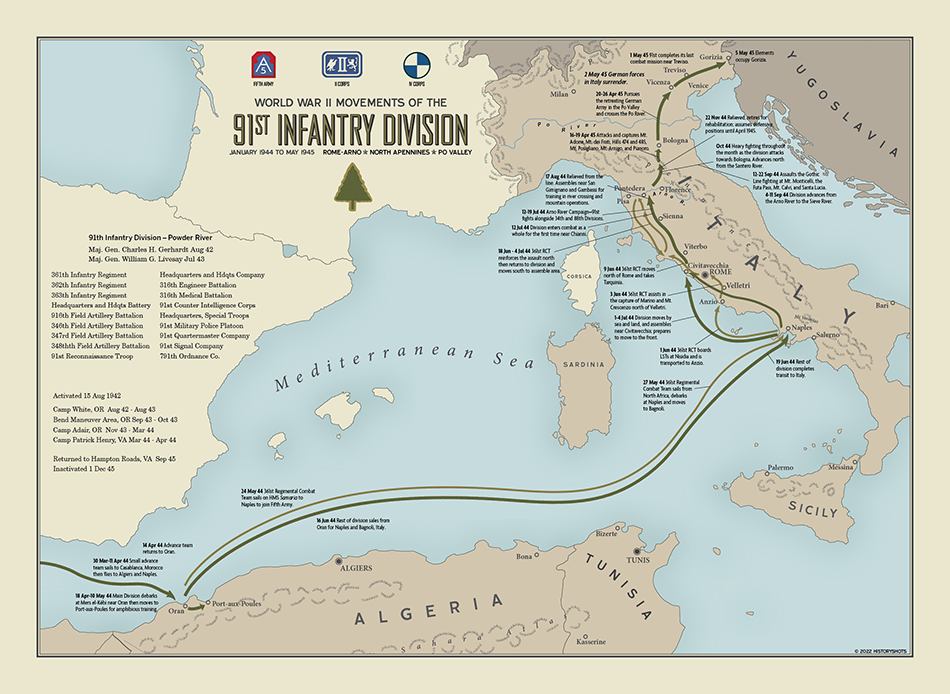

This campaign map shows the route of the 91st Infantry Division during World War II. This chart is available for purchase at HistoryShots.com.

Campaign History of the 91st Infantry Division in Word War II

Activation and Training (1942–1944)

The 91st Infantry Division, nicknamed the Powder River Division with the motto “Let ’er Buck,” was reactivated at Camp White, Oregon, on 15 August 1942. Its cadres came from the 1st Cavalry Division, and new recruits were drawn from across the West Coast. The division undertook intensive training, including a 91-mile march through the Cascades and maneuvers at Bend, Oregon, before transferring to Camp Adair. In the spring of 1944, it staged in North Africa and practiced amphibious landings at Arzew Bay. By June 1944, the division sailed to Italy, landing at Naples and joining Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army.

The 361st Regimental Combat Team (RCT) (June 1944)

The 361st Regimental Combat Team (RCT) of the 91st Infantry Division was among the first elements of the division to enter combat in Italy. Arriving in the theater in early June 1944, the regiment was attached temporarily to veteran units of the U.S. Fifth Army to gain combat experience. On 1 June 1944, the 361st RCT landed at Anzio, where Allied forces had been locked in a bitter stalemate with German defenders since January. Immediately upon arrival, the regiment was committed to action on the Anzio front. Within days, on 3 June, the 361st participated in the final breakout battles near Velletri, south of Rome, pressing German positions as part of the coordinated drive to liberate the capital.

As the Allies pushed forward, the 361st moved rapidly through the Alban Hills and into the approach routes toward Rome. By 4 June 1944, the Eternal City was liberated, and the regiment was part of the sweeping advance northward. These early combat operations blooded the 361st RCT, forging its reputation as an effective fighting unit before the rest of the 91st Infantry Division joined the front later in the month. Its baptism at Anzio and Velletri set the stage for its subsequent role in the Italian Campaign.

The Arno River Campaign (July–August 1944)

The 91st entered combat as a division on 12 July 1944, attacking German positions near Chianni. The 362nd Infantry Regiment fought its first action under artillery and tank support, while the 363rd Infantry seized hills dominating the area. By 16–18 July, the 361st Infantry pushed through Pontedera to the Arno, earning the distinction of being the first Fifth Army unit to reach the river.

On 18 July, a bold maneuver by Task Force Williamson (built around the 363rd Infantry) captured Leghorn (Livorno), securing a valuable port. By 24 July, the division’s patrols reached the outskirts of Pisa, braving artillery fire while protecting cultural landmarks such as the Leaning Tower. By month’s end, the 91st had established positions along the Arno, where it conducted reconnaissance and prepared for mountain fighting.

The Gothic Line (September–October 1944)

In early September, the division crossed the Arno and advanced through the Sieve Valley toward the German Gothic Line, a fortified barrier in the Apennines. The main attack began on 10 September 1944.

The 363rd Infantry assaulted Monticelli Ridge, a 3,000-foot peak studded with pillboxes and mines. After days of bloody combat, Company K captured the crest on 17 September, supported by artillery.

The 362nd Infantry struggled up Monte Calvi, while the 361st Infantry fought for Hills 844 and 856. Despite fierce resistance, the 91st broke through, securing Monticelli by 18 September.

By 22 September, the division had reached the Santerno River, and by month’s end, it had advanced north of Futa Pass, approaching Bologna. Fighting in this period was described as “lifetime days” of exhaustion, fear, and courage, with German counterattacks repeatedly repulsed.

In October 1944, the 91st faced one of its hardest battles at Livergnano, a cliffside village on Highway 65. The combat earned the nickname “Little Cassino”: entire companies were cut down by machine-gun fire and demolished by tanks. After relentless attacks, supported by massive artillery, the division secured the position. By late October, the advance stalled short of Bologna, and the division dug in for the winter.

Winter in the Apennines (Nov 1944 – March 1945)

For months, the 91st endured harsh conditions in the mountains. Snow, mud, and freezing rain made supply and patrol work grueling. The division held its lines aggressively, conducting raids and reconnaissance but unable to push further until spring. These static months inflicted heavy strain but kept German forces pinned in place.

The Po Valley Offensive (April–May 1945)

In April 1945, the 91st joined Operation Grapeshot, the Allied final offensive in Italy. Beginning 15 April, the division stormed out of the Apennines along Highway 65.

On 21 April 1945, the 91st entered Bologna, fulfilling the long-delayed objective from the Gothic Line battles.

On 23 April, it crossed the Po River, establishing bridges and capturing thousands of prisoners.

On 26 April, it crossed the Adige River, pushing rapidly through the Veneto.

By 2 May 1945, the German armies in Italy surrendered unconditionally

The Powder River Division ended the war in northeastern Italy, performing occupation duties around Trieste and Venezia Giulia.

Casualties and Honors

Over 271 days in combat, the 91st Infantry Division sustained heavy losses: 8,744 battle casualties, including about 1,400 killed. Its soldiers earned distinction for bravery. Two members received the Medal of Honor:

Sgt. Roy W. Harmon (362nd Infantry) – posthumously honored for single-handedly silencing three machine-gun nests on 12 July 1944.

Sgt. Oscar G. Johnson, Jr. (363rd Infantry) – for holding Monticelli Ridge alone for two days against overwhelming attacks in September 1944.

Numerous others received Distinguished Service Crosses, Silver Stars, and Bronze Stars.

Conclusion

From its baptism of fire near Chianni in July 1944 to the final crossings of the Po and Adige in April 1945, the 91st Infantry Division proved itself in some of the hardest fighting of the Italian Campaign. It achieved key “firsts” (first to the Arno, capture of Leghorn), broke through the Gothic Line at Monticelli Ridge, endured bitter combat at Livergnano, and spearheaded the liberation of Bologna and the drive into the Po Valley.

The division’s record demonstrates endurance, sacrifice, and effectiveness in a theater often overshadowed by other campaigns, but where Allied victory was crucial to the collapse of Axis defenses in Europe.

Organization of the 91st Infantry Division

361th Infantry Regiment

362th Infantry Regiment

363th Infantry Regiment

Headquarters and Hdqts Battery

916th Field Artillery Battalion

346th Field Artillery Battalion

347rd Field Artillery Battalion

348thth Field Artillery Battalion

91st Reconnaissance Troop

Headquarters and Hdqts Company

316th Engineer Battalion

316th Medical Battalion

91st Counter Intelligence Corps

Headquarters, Special Troops

91st Military Police Platoon

91st Quartermaster Company

91st Signal Company

791th Ordnance Co.

Date Activated is the date the division was activated, reactivated or inducted into federal service (national guard units).

Casualties are number of killed, wounded in action, captured, and missing.

The dates after the campaign name are the dates of the campaign not of the division.

The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States; The 91st Infantry Divisions in Word War II, By Major Robert A. Robbins, 1947; The Story of the Powder River Let 'er Buck, 91 Inf. Div., August 1917-January 1945 By United States. Army. Infantry Division, 91st · 1945